At the beginning of March, New Jersey school districts were notified that they should plan for closures due to a health emergency. Most teachers were given some time to prepare lesson plans for these closures around mid-March. Many districts had a one-to-one program in place, where each student was given a district provided device to use at home. These districts migrated to distance learning by using existing online learning platforms such as Google Classroom, Canvas, or Schoology. In the Pequannock Township School District, we freed up two mornings to give teachers time to create plans for the school closures. We went virtual, with a daily schedule that imitated the school day, starting on Monday, March 16.

For this article, I interviewed students and engaged with teachers; I was interested to hear how the school closure served as a catalyst to expand the use of educational technology. But in numerous discussions, I found that our students, teachers, administrators, and communities were not necessarily interested in expanding uses of educational technology. Instead, they simply wanted distance learning tools that could provide a sense of normality in delivering the same shared public-school experiences that we’ve lived for generations.

From the beginning, teaching online (especially for grades K-5) proved to have challenges for both teachers and students. These included taking care of family members during instructional times (including home interruptions from young children who were also at home); staying sedentary in front of a computer for more than four consecutive hours; losing the proximity and ability to “read students,” making it hard to change instructional direction in a lesson that wasn’t connecting with students; and not being able to provide immediate feedback and guidance to every student.

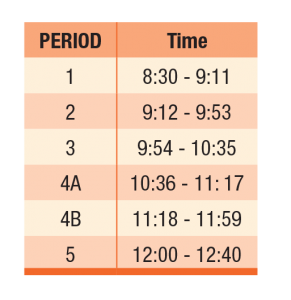

Online Routines At the onset, to simulate the normal school day, many districts set schedules and attendance requirements for students. For example, on day one, Pequannock set the four-hour daily middle school schedule shown here.

Students were expected to log in and attend their regularly scheduled classes so that teachers could take period-by-period attendance. Every principal started the day with a morning news announcement; our high school principal, Richard Hayzler, provides some terrific examples @RichHayzler; others can be found here: Morning Messages That Motivate.

Through these routines, students reported that they “go to the same classes online as the ones I would go to on a regular school day.” Yet students also acknowledged “online classes are different from regular classes as nothing is on paper or hands-on, and we do not have a teacher in the same room as us. Also, in gym class, we are responsible for exercising on our own instead of them telling us what to do.” Within class periods students reported “using Zoom and Google Hangouts a lot in all my classes too.” Expectations in these first two weeks were to run the sprint; take attendance, continue teaching all of the classroom content as normal, and track student progress.

Classroom vs. Online Differences Even during the first two weeks, the differences between regular classrooms and online classrooms became apparent to students. For example, virtually gone were the unintentional conversations and relationships forged by happenstance. As one elementary student put it, “in school, I usually talk to a lot of people and doing online school has limited the number of people I talk to from that environment. The only people from school I have really talked to so far have been my close friends. It is not too different talking to them because I usually contact them online when I am not with them in person.”

As an eighth-grader reported, students “interacted with peers much more in school compared to out of school. I can’t connect with my peers besides texting and Facetiming my close friends.” Zach, a middle school student, reported missing the camaraderie of physical interactions. “It’s very different with no physical and human interaction,” he said, “I used to talk to my friends (in person), give my friends a fist pump. I love being with my friends, and talking to them. I can’t do that now.” While students say they continue to engage with their circle of friends, missing was the casual opportunity to engage with others, or to start up a conversation with peers outside of your clique.

Students also reported that online interactions with teachers were different from their online classrooms. Generally missing were daily teacher feedback and interactions. “If we have a question, if we are having difficulty doing something, or I have to tell my teacher something, we have to contact them through Google Classroom or email and wait for their response instead of getting an immediate answer, which can get frustrating,” said one student. An elementary school student reported that “sometimes the instructions are unclear and we do not have a teacher to give us feedback when we think we are doing something incorrectly.” Zach further reported, “It’s hard for kids who have a hard time understanding a topic. I’m thinking that teachers should always have a video [to explain the process or topic] so that parents could watch the video with their students. They could also review it with parents.”

These narratives reveal a sense that distance learning environments make it much more difficult for teachers to pivot to answer questions, provide clarification, or to immediately redirect students to more successful outcomes. There was also a sense that instructional priorities needed to change.

Themes of Connection A recurring theme that was prevalent in all of the interviews and conversations was that of connecting through videoconferencing. “My favorite thing that I have done since attending online school has been doing video chats with my teachers and classmates because it is the only way we can really see them,” said one student. “Also, doing video chats, teachers are able to check in on us and we are able to tell them things that are happening in our lives. I think doing this has also helped us connect better with our teachers and fellow classmates.”

Richard Hayzler, the high school principal urged his staff to videoconference frequently. He told them, “Keep getting those virtual meetings in. The feedback from them is amazing. Our students need to see us. It comforts them.” You can see Hayzler’s YouTube channel by searching his name at YouTube.

By its nature, school is a social environment. Our kids and our teachers are missing that. Anything that adults can do to convey messages of hope, support, optimism, and resilience is meaningful and greatly appreciated by our learning communities.

During these stressful times it helps for everyone to keep in mind that families are juggling running the household, remote work, and caring for their children and older relatives who are most vulnerable. There are the many parents who work in healthcare, as first responders, or in other essential-worker occupations. All of these circumstances conspire to create exhaustion, anxiety and worry for families and students. Yet there’s a large pool of research to support the idea that supportive messages reduce attendance, engagement, and mental health issues. At this crucial time, when students are vulnerable, any way that we can leverage technology to lead with empathy and compassion and to keep our learning communities connected is appreciated beyond measure by our students.

The Role of Boards of Education in Supporting Distance Learning Rather than react to our current distance learning experiments with short-term solutions, it’s useful to learn from these experiences, engage in community discussions, and move forward with a strategic plan that applies best practices to meet the needs of our learning community. Within this context, research reveals a roadmap that illuminates a path forward. Research determines that at a minimum, a successful academic initiative contains the elements below.

- Visionary leadership and planning;

- Ongoing financial support;

- Equitable considerations;

- Early adopters;

- Professional development; and

- Routine communications with the stakeholders.

Visionary Leadership and Planning At its root, visionary leadership is expressed in the district strategic plan, which results from surveying the community and then building a coalition of community stakeholders to institutionalize what is an appropriate match for your district. The National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA) proclaims that effective school leaders “in collaboration with members of the school and the community and using relevant data, develop and promote a vision for the school on the successful learning and development of each child and on instructional and organizational practices that promote such success.”

Within distance learning, the plan might state that by the end of five years every K-12 student will have a district-provided device for distance learning.

Despite the growth of the BYOD (Bring Your Own Device), model, recent events have revealed how crucial it is for every student to have a district-provided device. For example, this spring has exaggerated the awkward classroom moment that takes place when a teacher asks a class to take out their cell phones to participate in an online survey. The student whose family can’t afford the phone, who didn’t recharge it, or who doesn’t have enough cell phone capacity to join in feels the social stigma of non-participation. In this crisis, the districts that didn’t provide a district device to each student have come to understand the digital divide inequities as they resorted to distributing paper packets of materials. Students with district-provided devices had the potential to continue daily classroom routines such as recorded lessons, classroom meetings, and individual conferencing. These activities are the tenets of our public education — human interactions that nurture lifelong learning.

District-Provided Chromebooks: A Routine and Normality Our district is in its fifth year of providing Chromebooks to every K-12 student, following the 2014 district strategic plan. These Chromebooks were set up with standard icons including Google Mail, Classroom, Drive, Meet (now with Grid view for video conferencing), Jamboard, etc. For years now, our students has been building a comfort level — guided by their teachers — by navigating through these standard programs during their daily classroom routines.

Yet at the beginning of our school closure our K-5 devices didn’t originally go home. Although every K-5 student was assigned a Chromebook, they were locked up in their classroom laptop carts. Over these past few weeks I’ve had numerous interactions with parents who showed up to the pick-up window to borrow a Chromebook for their K-5 student, generally out of exasperation. These families understandably thought they could get by using home devices. But parents became frustrated trying to find and set up the common district apps. Families that picked up the district Chromebooks said they were amazed at how easily K-5 children engaged in morning meetings with their teacher, enjoyed read-alouds, or broke into groups to work on a Google Doc. One Colorado parent recently wrote in Educational Leadership magazine, “Every day (his teacher) meets virtually with my son to keep a routine that he loves so much — calendar time. It may seem trivial to many, but calendar time — with dancing, show-and-share, and more — is so much to a five year old! Not only does he get to see his teacher smiling, he gets to see his 12 best friends that he’s spent the past eight months with. The giggles and smiles are priceless!” In short, these district Chromebooks provide a comforting sense of the everyday schedule.

Ongoing Initiative Financial Support Funding such a K-12, 1:1 initiative takes rigorous prioritization of a 1:1 program over time. Building a long-term funding commitment to technology capacity can be hard. Given that the majority of board members, superintendents and administrators serve less than eight or twelve years, long-term funding for something like a device initiative must be compelling enough to transcend leadership turnover. To preserve the collective memory, these financial commitments must be embedded into the fabric of long-term plans that are agreed upon and approved regularly.

Equity Considerations Visionary leadership dictates that a district device must be provided to every child to successfully participate in distance learning. Districts must also make sure that all students have robust wireless access at home. As Anthon Rebora states “If one of your students doesn’t have internet access, you essentially proceed as if no one did.” While home access considerations are beyond this article, there are some good resources for home internet and wireless access on the NJSBA COVID-19 Resource page under the “Technology” heading, and in the NJSBA webinar, “A Day in the Life of a Distance Learning Student,” that was broadcast on April 2.

Early Adopters On March 11 and 12, just before the school closure on March 16, our district provided two half-days of professional development to prepare our teachers for two weeks of distance learning. During one of these days I walked into a math department meeting to observe teachers engaged in sharing online resources. In addition to the math supervisor, spearheading this effort was Chris Kirkland, a high school Algebra teacher. He was busy training other teachers in the use of Doceri and Jamboard (along with Google Meet/Grid View)—digitally shared whiteboards that allow students to participate remotely. This group quickly turned more excited as they collaborated and experimented; concurrently adding their own notes to these virtual whiteboards.

Professional Development Kirkland happens to be one example of the type of early adopters and turn-key trainers needed for any successful, districtwide initiative. Yet Chris (@ChrisMKirkland) is also a product of years of districtwide technology professional development, which encourages staff to adopt more innovative uses of technology. The district holds the annual Pequannock Tech Summit, and champions districtwide digital learning practices at #pantherstrongDL, and on the district Twitter feed. Many of our staff have engaged in the rigorous process of obtaining Google Certified Educator status.

Routine Communications with the Stakeholders Routine communications within your community of learners provides additional evidence of successful distance learning initiatives. The results of this professional development, as in many successful school districts, are demonstrated through multiple district multimedia streams, from using Google Forms for Attendance, DoNows, and Assessments, to librarians creating YouTube videos to continue a sense of connectedness. District communication is evident in the numerous administrator email broadcasts, the shared messages of hope, optimism, and perseverance through YouTube videos, our supportive community Facebook groups, and our principals delivering daily morning news announcements. None of these practices would be on display today were it not for the firm commitment to adopt a culture of innovative use of technology that was baked into the district strategic plan more than four years ago.

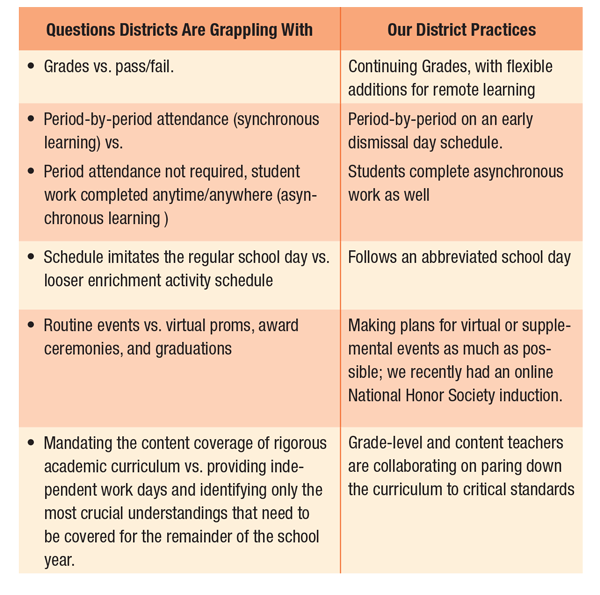

Status Quo Normality vs. the New Normality While our school closure started as a two-week sprint, as distance learning morphed into an indeterminate time, districts recognized that we are instead running a marathon. During this transition our districts are now grappling with questions of whether to adhere to status quo classroom conditions in place since the early 1900s, or embrace new habits and customs.

The chart above illustrates some of the questions districts must consider, and how our district is handling those issues. Different practices work for different school districts; this is merely what we have opted for at this time.

Through all these distance learning considerations, one theme emerges above all others. Students need to hear from adults. They need calls and videos from guidance counselors, teachers, principals, and superintendents; simple health and wellness check-ins. They miss opportunities to connect, in a physical space, with their teachers, and peers. Our most fragile and struggling learners need individualized breakout video rooms with adults. And most students simply need open video areas to chat with peers and continue the familiarity of their physical learning communities.

What Does Successful Distance Learning Look Like? It looks like continuous communication that connects our learning communities. It lifts the human spirit to drive optimism, resilience, persistence, and perseverance. Zach in middle school stated, “Even though I thought I would not get the same feeling while online, my favorite teacher still manages to tell us how much she loves us, how we’re going to make it through, how we should love honor and respect each other. She still manages to project her academic knowledge, about her life, and about her life’s journeys. I thought I would not get that feeling online.” One of our seniors put it this way: “Although I would so much rather be in school, I know that it is necessary to be home in order to keep everyone safe. My school district is motivating the students each day; we get morning announcements from our principal in video form. The superintendent is constantly reaching out to see if there is anything we need help with or anything that needs to be improved.”

Our public education system was founded on the principles of creating a skilled and educated populace. Within this mission, each generation subsequently sets the educational priorities that they see fit. I suspect that history will reflect on this time as a turning point where we relied on our educational technology to connect, communicate, nurture, support, and uplift our learning communities. I believe that we will witness a richer period, as suggested by John Dewey, who said “Education is a social process; education is growth; education is not preparation for life but is life itself.”

As board members it’s never too late to continue or plan to provide the types of nurturing, encouraging, distance learning environments that mimic the classroom communities that our students so desperately crave.

A complete list of references for this article can be found here.

Dr. Barry Haines is supervisor of instructional technology, media services and data management for the Pequannock Township School District. He received his Ed.D degree from Northeastern University; his thesis was on researching best practices of organizational leadership studies as they relate to educational technology. He is also a member of the Mendham Borough Board of Education.