In our October presentation at NJSBA’s Virtual Workshop 2020, we began our program with a short video made by a 15-year-old Canadian student who sits cross-legged, alone on her bed. The video dramatically illustrates a student’s weariness with pandemic school closures and remote learning.

First she surveys photos of the vibrant life she enjoyed before the pandemic. Then she opens her laptop and the dullness of being isolated for months, away from the life she loves, begins to overtake her. Days pass, her clothes change in rapid-fire fashion, but her face, for a long time, remains the same. Slowly, as time drags on, her mouth begins to quiver, her stoic expression dissolves, and she begins first to cry, then to scream, as frustration overwhelms her.

Polls and surveys are showing that the emotions expressed by the young woman isolated in her bedroom in the award-winning film, “Numb,” made by Liv McNeil, the Canadian teenager, reflect the stresses many students and teachers are feeling as the pandemic approaches the one year mark.

The Social Emotional Toll of the Pandemic An NJSBA report published on Jan. 27, www.njsba.org/StudentMentalHealth, found that 47.73% of the 264 respondents agreed with the statement, “We do not see evidence of more students in crisis, but in general students are more anxious and depressed.” Another 12.12% of the school board members, administrators and superintendents said, “Our district has seen evidence of more serious crises, such as incidents of self-harm, threats of self-harm, or hospitalizations.”

The report showed that, while a feared spike in suicides and other self-harming behaviors has not occurred in New Jersey’s public schools, students and parents are on edge.

Nearly 22% of survey respondents agreed with the statement “Many parents in our district have lost their jobs. Families are experiencing an economic crisis, and this has had a serious impact on the emotional stability of many children in our district.” Meanwhile, remote or virtual learning had “increased stress at home” for nearly 91% of the students’ families, according to the 264 school board members, administrators and superintendents who responded to the survey.

Around the nation, Education Week reported on Jan. 6 that “nearly three-quarters of teachers say their morale is lower than it was before the pandemic, and 85% say overall teacher morale at their school is lower now. Back in March, just 63 percent of teachers said morale was lower.”

Even some of the best teachers in New Jersey are hard-pressed to maintain their level of excellence in the classroom. In a pair of Education Matters videos described in the Feb. 2 School Board Notes, Kimberly Dickstein-Hughes, the 2019-2020 New Jersey Teacher of the Year, discusses how she struggles to teach her high school students in classes where most students are at home, learning remotely, while she is simultaneously speaking to a handful of students attending school in-person that day.

Angel Santiago, the 2020-2021 Teacher of the Year, in the same Education Matters video interview, says that his fifth-graders are struggling with their motivation to complete the work. The pandemic, he says, has required many students to take responsibility in ways for which they’re not developmentally prepared.

In the Jan. 27 NJSBA report, Howell Township superintendent Joseph Isola discusses the extraordinary pressures continuing to face teachers and students as the pandemic approaches a full year of academic disruption in New Jersey.

“In the world we’re living in, students’ levels of responsibility have been impacted greatly,” Isola said. Under normal circumstances, a fourth-grade student would get off the bus, show up at school, and have structure with their teachers and their peers. “That’s no longer the case,” he said.

Students are living with complicated schedules. Half days. Zoom sessions. Some days they’re in school, some days they’re not. “The flexibility we’re placing on students far exceeds their developmental readiness,” he said. “That’s a problem that creates stressors that they may not be mature enough to handle.”

In too many cases, Isola said, students respond by keeping their video off when they show up for class. This diminishes their ability to be present, to take part in conversations, and it prevents teachers from seeing how they are receiving the class material being delivered on any given day. The district, he said, reaches out to students and tries to find out what is going on in their lives to help them, but it’s a constant struggle.

Teachers are affected, too.

“Teachers want to be perfect,” Isola said. “They always feel like they’re being judged and evaluated. And there’s no way to be perfect, right? But in their own mind, they’re stressing about being as good as they were, before the pandemic. In this whole new world, they can’t be perfect, and it is eating them up.”

The truth about the state of education during the pandemic, Isola said in the Jan. 27 NJSBA special report, is that it is impossible to cover every aspect of education in the same way it was addressed when class was in session for in-person instruction.

“There’s no way we’re covering it all. Let’s be real,” Isola said. “We have fewer hours on task due to the pandemic,” he said. “There isn’t a way that what we are doing is equal to what we were doing (before the pandemic).”

How Districts Can Help Students and Staff As Isola notes in the NJSBA report, it is important to be sensitive to the stresses on both students and staff.

We also believe that prioritizing social and emotional learning (SEL) programs is critical, as are practices such as expanding the time for teachers and students to participate in unscheduled meetings and discussion. School districts should seek out ways to individually connect with students and families.

Within the classroom, striving for more small group instruction — perhaps through Zoom or Google Meet breakout rooms — can help build the important relationships that are at the foundation of learning.

Teachers, who have been struggling with endless days in front of a computer, childcare issues and sometimes dealing with household members sick with COVID, also need social-emotional care. Boards need to send teachers messages of support and gratitude.

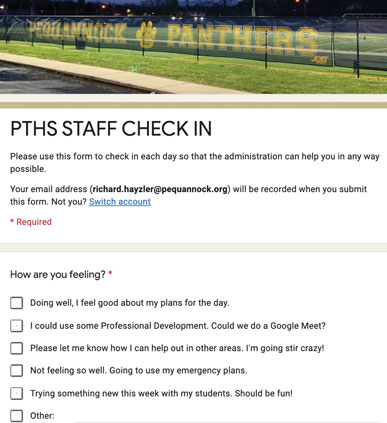

Richard Hayzler, principal of Pequannock High School, suggests regularly checking on the social-emotional needs of the district staff. To that end, he uses the form, at right, to routinely gauge the well-being of his staff.

Scaling Up Technology Resources Despite everyone’s desire to return to the classroom as soon as safely possible, virtual learning is here to stay. It will be immensely useful in the future — especially in situations such as snow days, for homebound students and those students who may need extra help or personalized learning.

To continue to build these virtual learning communities, we must rely on our district technology departments. Over the last year, most IT departments have been under inordinate demands.

There is a benchmark, which is widely considered archaic, that says there should be one IT helpdesk support staff person for every 500 devices (1:500). Yet even by those outdated standards, many districts do not measure up. Many districts deploy over 1,000 student and teacher devices for every one IT helpdesk/support staffer.

In addition to devices, adding hardware to the network (HVAC systems, security cameras, wireless access points, etc) and mandating that remote computer devices are repaired in a timely manner greatly increases the workload on these departments.

As a board member in an average district of about 2,500 students, it’s appropriate to think of your IT department as equivalent to supporting a typical Fortune 500 company or small community college. Your IT staff not only supports all of the in-house and remote hardware and software (from kindergarten tracing apps to Google Suite, CAD, coding, robotics and STEM), they also support the operations that a typical family has come to expect, such as emergency notifications and round-the-clock access to the website, assignments, grades, progress reports, and report cards. The next time you receive or access any school communication on your phone or computer, remind yourself of this essential IT support. Boards should be prepared to support their IT staff with the resources necessary to provide the services that your community requires.

Chromebooks: It’s All About Processing Power The Chromebooks that are found in many districts are another technology consideration districts need to plan for.

Chromebooks were never meant to provide high-quality video and audio-conferencing capabilities. Over the last several months, districts have been frustrated by experiences of disastrous videoconferencing. While the problems were initially blamed on poor bandwidth or weak wireless signals, in many cases, the real problem may be with Chromebooks, which have lower processing power. Teachers are better served with a quality laptop with a better video camera and processing power.

A Chromebook has a lifespan of about 4-5 years. In addition, about 7%-10% of a district “fleet” of Chromebooks is damaged every year due to things like cracked screens and broken power cords.

Districts might consider defraying repair costs through family device insurance plans (Hillsborough Township public schools uses this program: Tech@Home – Protection Plan), and ensuring devices are replaced annually for a total refresh of the fleet about every four to five years.

Additional Hardware Many districts have come to realize that teachers need several items for successful remote instructional practices, including:

- A laptop, for the increased processing power and a good quality, built-in, videoconferencing camera

- A large monitor/display hooked up to the laptop (usually HDMI), enabling the teacher to view students in the classroom view on the laptop screen, and the instructional (handout, slideshow, whiteboard) on this second attached monitor.

- A secondary device (such as a Chromebook) as both a backup, and to enable the teacher to view and attend the class as a student participant.

- A document camera so the teacher can display a document or object to an audience.

- If needed, a robust wireless access point, provided by the district.

This basic, remote setup is needed for both the teachers, administrators, and any additional instructional aides.

Professional Development, Professional Development, Professional Development The only way for teachers to adopt new tools like cutting-edge hardware and software for classroom practices is through professional development.

Many school technology budgets fund for 50% hardware and 50% software, based on a four- or five-year replacement cycle. Professional development is often an afterthought. A better technology budget funding formula would be one-third for hardware, one-third for software and one-third for professional development.

A key question for district strategic planning might be, “How do we provide differentiated, targeted professional learning opportunities for our teachers?”

One useful strategy, which provides top-down support for bottom-up change, involves giving teachers the opportunity to share best and successful practices, while still allowing administrators the freedom to provide new and engaging opportunities for professional development.

So educators must continue to improve their virtual instructional techniques, and do so with better and more reliable hardware and software.

This must all be done while keeping in mind that engaging with students and building supportive relationships with them are at the foundation of learning.

As your districts look ahead to a brighter future, educational leaders everywhere need to collaborate, and to provide each other with exemplary models of success. That is both our immediate priority — and a lasting lesson for the future.

Dr. Barry Haines is the director of curriculum, instruction and operations for the Ridgefield Park School District in Bergen County. He is also a member of the Mendham Borough Board of Education. Bruce Reicher is a technology teacher in the Upper Saddle River School District in Bergen County, and a member of the Hawthorne Board of Education in Passaic County. Additional reporting on this story was done by Alan Guenther, NJSBA assistant editor.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Barry Haines’ article “Striving for Normality: A Day in the Life of a Distance Learner,” which provided a look into the remote-learning experiences of students and teachers, appeared in the May/June 2020 issue of School Leader magazine. The issue is archived here.